Researched and written by Timothy Foley

The cone snail is a venomous mollusc found in tropical oceans. It lives in shallow waters near coral reefs or under coral shelves. Its conical shell is long and narrow, and has colourful patterns on a white background.

The patterns on cone snail shells are caused by several chemicals interacting when the snail is an embryo. Some chemicals inhibit the production of others (inhibitors), whereas other chemicals activate the production of others (activators). A combination of activators and inhibitors can cause chemical oscillations (or waves), which result in “regular” patterns of stripes or spots. These patterns may not look regular, but are predicted by equations derived by Alan Turing in the 1950s. Long, parallel waves produce stripes, whereas a second set of waves (at an angle to the first) can cause the stripes to break up into spots.

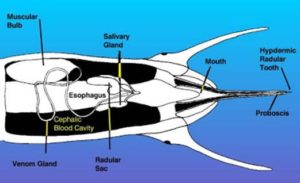

The cone shell is either buried in sand and stones, or encrusted with coralline algae for camouflage. Cone snails vary widely in length from 1 to 22 cm. They have a strong muscular foot, which allows them to travel in search of prey. Most other gastropods have a radula consisting of a series of small teeth arranged along a ribbon which is used to scrape off food. However, in cone shells the radula has become modified so the ribbon is reduced and the teeth have become hollow harpoons stored in the radula sac, except for one tooth attached to the proboscis. They have eyes halfway down their two tentacles and a flap of tissue called the mantle, which lines the inside of the shell. Part of the mantle is rolled to form a coloured siphon, which extends out from the shell and draws water into the gills, thus allowing them to absorb oxygen from the water.

Hunting

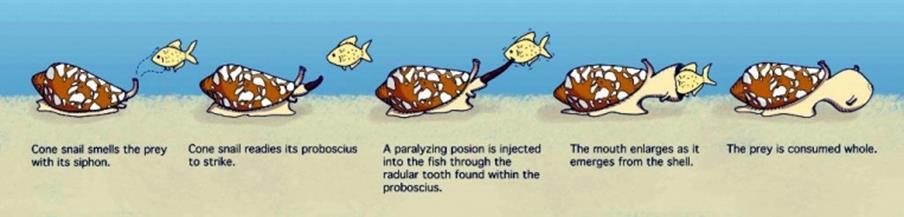

Cone snails hunt at night, but a few species also search for prey at dusk and dawn. They have an unusual way of hunting. They pick up the prey’s scent with chemo-receptive (scent) cells on their proboscis. When their proboscis gently touches the prey, their radula rapidly fires, injecting their prey with toxic venom and paralysing them within seconds. The radula is then retracted via a thread which prevents the prey from escaping. The whole prey is then engulfed through their expanded proboscis, and is moved to the stomach for digestion.

A second approach to hunting is to release a potent form of insulin into the water, which subdues the prey before they reach it. For example, the Geographer’s Cone Snail uses chemicals that cause a drop in the fish’s blood sugar level (hypoglycaemic shock). This approach can send a whole school of small fish into shock. The snail then engulfs its prey while it is subdued.

The use of a firing radula makes the cone snail one of the fastest hunters in the animal kingdom. The average attack lasts only milliseconds. Piscovores (like the Geographer’s Cone Snail) have the most toxic venom, whereas vermivores (e.g. the Imperial Cone) have the least toxic. The venom has a very complex chemical makeup which varies widely between species, and can even be different for each individual attack.

Cone Snail Groups

Cone snails are divided into three groups based on their diets: Piscivores (fish eating), vermivores (worm eating) and molluscivores (snail/mollusc eating). Each species of snail has different adaptations depending on the food it eats. Piscivores have teeth with a long smooth shaft, tipped with long curved barbs (sharp hooked points). Vermivore teeth are broader, short and strongly serrated, whereas molluscivore teeth have heavy barbs near the base, and are serrated along the shaft.

Eggs

Cone snail eggs are fertilised internally, rather than being released into the ocean. The female lays egg capsules, each containing several eggs. These then hatch as either free-swimming larvae or baby snails.

Toxicity

Although cone snails appear harmless, they are in fact among the most toxic animals in the world. There have been over 30 cases of human envenomation, with several fatalities. Their venom consists of hundreds of active components which inhibit the transmission of neuromuscular signals in the body.

There is no known anti-venom. A sting causes tingling and/or numbing, which spreads to the whole body. However, more positively – in 2005, two new drugs were chemically synthesised from cone snail venom and used to treat severe chronic pain. They are reported to be 50 times more effective than morphine.

Further Information

A video explaining more about cone snails can be found here.