Written by Bryan Popple & Kathleen White, January 2020

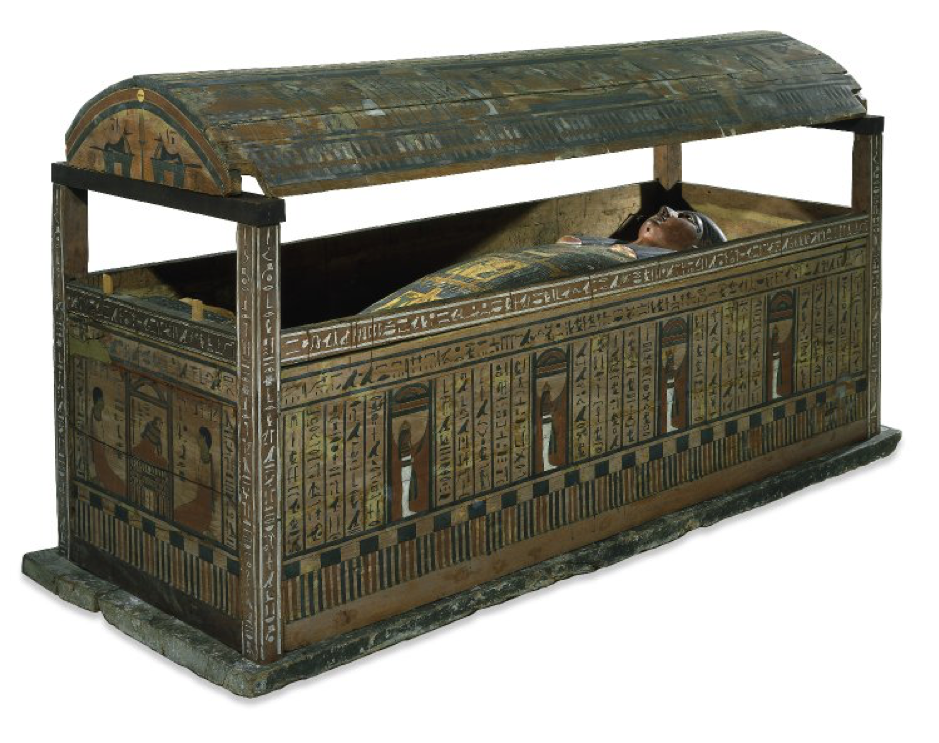

Research has been ongoing into how Tahemaa came to the UK circa 1824 as the purchase of an English scholar who stopped in Egypt on his way to India. The buyer was John Fowler Hull, born to a well-off Quaker family in Uxbridge in 1800. John didn’t go into the family milling business or into banking, like his other relatives, but instead studied languages. He learned 30 languages, including Greek, Latin, Bengali, Sanskrit, Malayan, Coptic, Ethiopian, German, Spanish, Russian, and Portuguese, choosing to correspond in Latin with his friends. Between 1820 and 1822 he divided his time between Uxbridge and Paris, where he had a number of language tutors, including an Egyptian who had been one of the oriental interpreters at the court of Napoleon, to help him learn Arabic and other Eastern tongues.

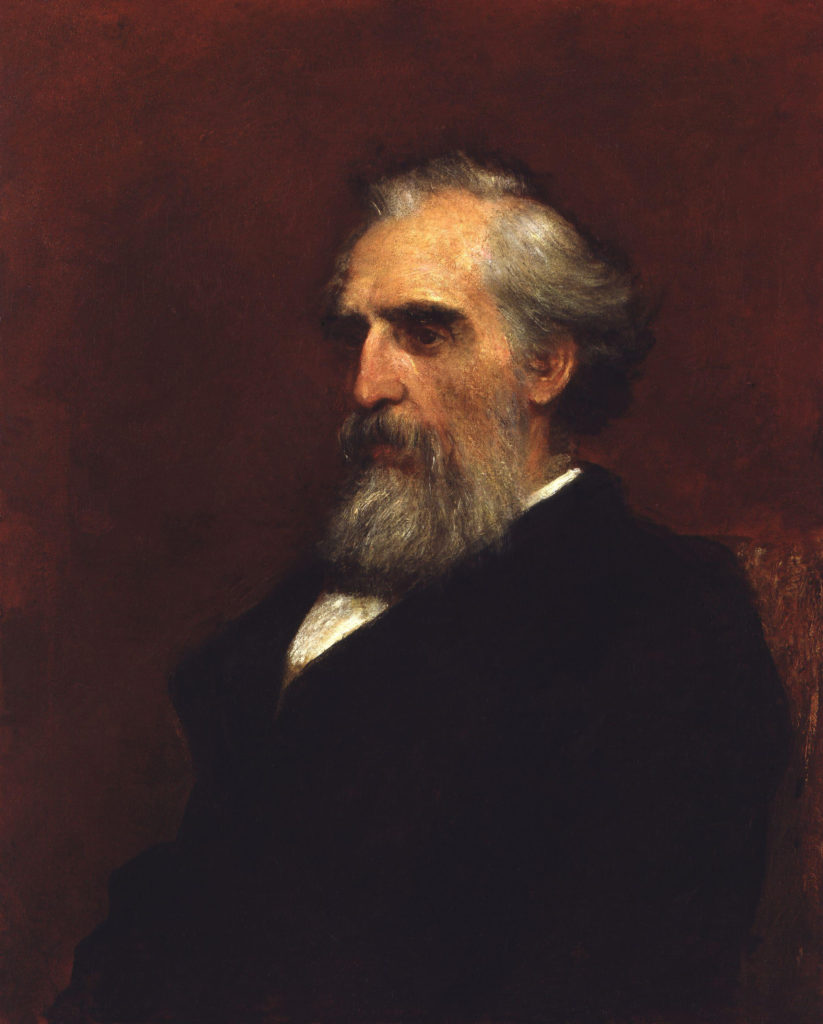

John Passmore Edwards (1823–1911), portrait by George Frederic Watts, 1894

John had the money to travel widely, and as he did he collected manuscripts and books, many of which he bequeathed to the British Museum. In 1823, on his way to India, he stopped in Egypt and travelled to Thebes (Luxor), where he purchased the coffins of Tahemaa and her father Hor, which were shipped back to Britain while he continued on to India. His studies took him first to Bombay, then to Darwar, with plans to travel to Madras and Calcutta, but he was taken ill in the village of Sigaum, just south of Darwar and died on 18 December 1825, before medical help could arrive. In his will, he left over 120 manuscripts and 600 volumes of printed books to the British Museum. Both mummies were left to his brother Samuel Hull, a banker in Uxbridge.

The mummies disappear from sight until 1880, when Samuel died and his estate came up for auction in Uxbridge. Almost nothing remains on record about Samuel, but we do have records of the auctions where his property was sold – which was considerable, including many ground rents, houses, residences and land – but also 2 Egyptian mummies. John Passmore Edwards, MP of Salisbury, bought both mummies, donating Tahemaa to the Salisbury & South Wilts Museum and Hor to the British Museum.

Going back to John Fowler Hull, there is still much to discover, including the journal he kept on his travels, left in the hands of friends and which may give us clues to Tahemaa’s origins in Thebes. One friend, T. Grimes, wrote a ‘Biographic Memoir of Mr. John Fowler Hull’[1]. It was clear he was considered a genius by his colleagues, although Grimes notes:

“… however great his attainments in learning were, they were equalled, if not excelled, by a uniformly kind, amiable, and unassuming disposition, perhaps never surpassed by any other individual. His company was enlivening by a ready and playful wit. His generosity was unlimited; and, being in the enjoyment of a considerable income, he was able to dispense his bounty with a liberal hand… The poor in his neighbourhood have cause long to remember him, while many charitable institutions have not escaped his notice and liberality.”

___________________________________________________________________________

[1] T. Grimes, The Oriental Herald, and Journal of General Literature, Vol. XX, January to March, 1829 (London: W. Lewer, 1829), pp. 303–310.